Our collective grief at the senseless felling of the Sycamore Gap Tree sits atop an uncomfortable truth.

Contemplating responsibility and legacy

Hi friends,

The desecration of the Sycamore Gap Tree in Northumberland has prompted the sharing of a piece I wrote about a pair of felled trees that meant a great deal to my family and families before mine. It speaks to the place trees hold in our collective imaginations. Our sense of identity. The events we imagine they oversee and the protection we believe they afford us, however irrational.

It also asks us to consider what we do with our grief in times like these. Whether our national tendency towards mythologising distracts from our collective responsibilities.

For it’s never really about one tree.

This week’s letter is free to read, so please share with anyone you think would resonate. I’m also offering 25% off an annual subscription for this week, marking the start of the Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival. This year’s theme is REVOLUTION, which feels as relevant as ever.

Legacy

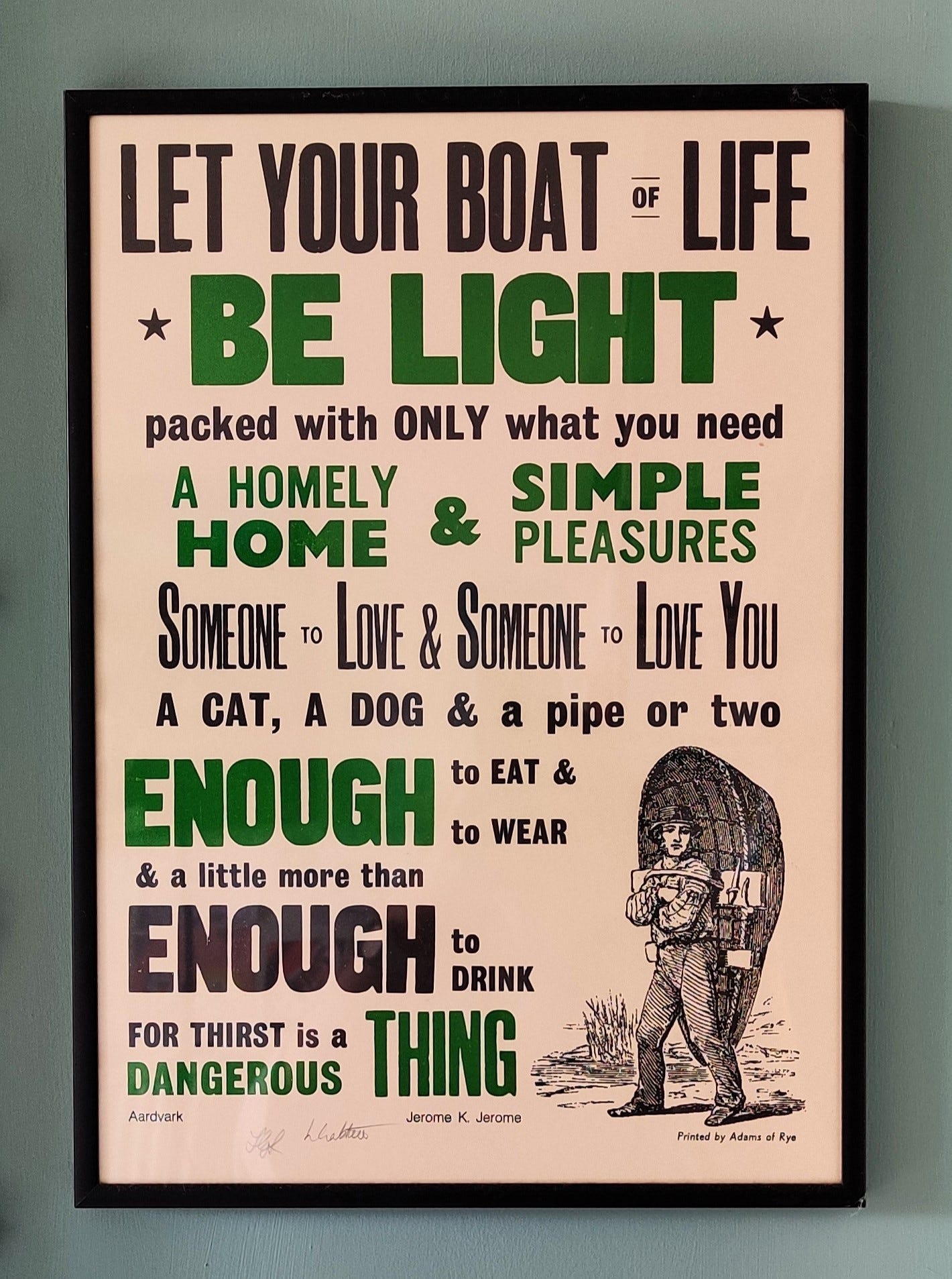

Ten years ago – save a week – we drew up outside our new home; our impractical three-door car sitting low on its wheels stuffed with valuables we couldn’t trust to the movers. Valuables that included our 16-week-old daughter. The cat. The wedding album. A print gifted at that wedding 12 months earlier, framed behind the thinnest of glass. ‘Let Your Boat of Life be Light,’ it said.

Our boat felt anything but.

That evening, we avoided the boxes. A fish supper on my lap, I sat on a folding chair on our front lawn catching the last of the sun as it peeped out momentarily in the space between trees and hedge to illuminate the budding bluebells growing in clusters across the grass. Greens and blues look brighter as the light fades. There’s some science to it, though perhaps I was also seeing things in technicolour owing to the sense of occasion the day afforded.

I swapped the remnants of dinner for my daughter, newly fortified for another of the evening’s cluster feeds. Patting her cloth-nappied bum in relief when she settled quickly, I fixed my attention on the low-hanging branches of the pair of trees that stood sentinel a few metres away from either side of our front door. Some weeping variety I couldn’t then name and which – slow to come into leaf – were still bare that early April evening. I glanced around; my untrained horticultural eye taking in the more familiar markers of the season. Yellow gorse. Delicate cherry blossom.

Our gorse. Our blossom.

There would be a lot to learn about this garden, this house. We were, happily, ‘home’. Though as I was passed my glass of celebratory fizz, I intuited it would take some time before it really felt like it.

Today is a Thursday. A non-working day for me. I’ve returned from my round trip to the bus stop more harried than I’d like. A forgotten ‘something’ had stopped my 10-year-old in her tracks halfway along the street, propelling her on long legs homewards and back again just in time to catch her ride to school. And before that, there had been a delay of my doing. A need for photographs. Not because this date held any particular significance. Not a birthday. Not the first day of a new school year. But, rather, the last time my daughters would see those two gnarly guards standing tall before our home.

“Cuddle them!” I’d ordered from behind my phone as I attempted to get it to focus on children and trees near and far. “Look sad!” The girls complied as I snapped away. We’d then paused to pat their bulbous, damp trunks in farewell before I checked my watch and hurried them bus-wards.

“Bye trees!” shouted my younger daughter over her shoulder. “You’ve had a good life!”

And - I suppose for the most part - they had.

It takes three tree surgeons a matter of hours to reduce them to a pile of firewood. My husband keeps the wider family appraised of progress, periodically reporting on the workers’ responses to his instructions: watch our budding lilacs; keep a sizeable chunk back that we can refashion into a bench. His request to be left the bulk of the offcuts for drying and burning has been met with a chuckle. “You sure you don’t want us to take it? We’ll sell it back to you, no bother!”

As the clear-up nears its end, I stand on the front step and look at a view I’ve never seen before. It’s a view that takes in the hotel over the road – ‘the old Marie Stuart,’ as locals are wont to call it – and wonder when in the past hundred or so years the house was last so exposed to the street. Those trees offered more cover than I’d appreciated.

A neighbour passes by. I tell her about the morning’s event by way of a greeting. “It’s always so sad when a tree has to go,” she laments. I knew she would and part of me needed to make clear we wouldn’t be chopping them down unless it was unavoidable. We’re not that kind of couple. No decking. No ripping up of lawns to be replaced with no-mow Astroturf. We’d always spoken about being custodians of this house. This small patch of land. We’d never thought it ours to do with as we pleased.

We’d noticed the trees weren’t behaving a few years ago. Even later to bud, we wondered if it was a consequence of climate emergency or just a natural fluctuation in their life cycle. Then we noticed the trunks appeared swollen, sprouting thin branches we thought might be new, but then again we couldn’t be sure. What about those dark patches on the leaves? And the volume of dead wood on the lawn? Maybe they’d always been like this, we wondered. We’d been busy with the babies and the task of breathing new life into the old house. We could be excused for our lack of vigilance.

But then, during my daily walks around Queen’s Park last winter, I arrived at a diagnosis. Similar trees had been condemned by the Council; victims to savage southern spores that had destroyed them from the inside out. By the time ash dieback was confirmed, it was too late; their disease had already been carried uphill on the breeze to infect ours. I reported my findings to a spouse who didn’t want to believe it. Ours weren’t ash, he said, thrusting a screenful of Google images at me. But they were the same as the weeping ones in the park, I argued back. The ones whose pustulous trunks were bound in crime scene tape and rain-moistened posters announcing they’d be felled by spring.

A month or so passed and the last of winter’s gales ripped yet more sorry branches for us to gather come morning. They were becoming a liability. What if they fell on the house in the next storm? What did our insurance policy say about trees, exactly? After a last-ditch attempt to argue they might be part of the small minority of trees to eventually recover from the disease, the sceptic acquiesced – as was his way – and booked the tree surgeons.

That evening, I stood at our bedroom window looking out over the highest of the branches. These trees meant home to me. They were home to the blue tits I could see hopping from branch to branch pecking at the tiniest insects, too. My chest heaved in resignation as I pulled the curtains shut.

By early afternoon, the guys dispatched with only the most rotten of the wood, I wander over to one of the stumps to have a look at what’s left. “God above – they absolutely stink!” I say, vindicated, as I catch a whiff of their rot. I imagine the roots radiating out and down like an invisible mirror of the branches that used to shade me. How far do they run? And how long before they shrink back towards what’s left of the trunk before beginning their centuries-long decomposition? I hunker down and embark on the task of counting the rings. My husband’s eye for detail has been letting him down so I order him inside to retrieve his reading glasses, without which he’s no help whatsoever.

“I’ve counted about 140,” he says, after a while. And I agree. Planted in the 1880s. The Lowther era.

I’d had another plan for this afternoon but find myself waylaid as I contemplate the planting of these trees and all they must have stood over at the top of this hill. When we first moved in, I’d been consumed with finding out as much as I could about the house’s former inhabitants; any interest in my own family tree replaced with the desire to breathe life into the stories of strangers. It had offered the hope of a more palatable one to weave my own life into. I lost hours forming meaning from census and valuation rolls I’d scoured the internet to find, and it’s that sheaf of papers I go looking for now.

The disorganised, tea-stained pile is eventually located beneath the coffee table alongside a dusty pile of unopened New Scientist magazines. ‘Climate Slowdown: Is It Time to Stop Worrying about Global Warming?’ reads one front cover from December 2013. We hadn’t even removed it from its now-absurd plastic wrapper. Old science. A relic from an optimistic past.

I leaf through the sheets again, looking for Lowther.

The Lowthers lived in the house in one permutation or another from around 1882 until 1915 and were the third family to occupy the house following its completion in 1863. I’d found more information on this clan than any of the others; my trails on the Conleys and even the Copestakes running cold before long. Along with their four children, Richard and Helen Lowther moved to the street from 3 Cathkin Terrace in Mount Florida.

As I adjust my eyes to the antiquated writing on the Census for 1881, I remember afresh my mounting frustration as I’d scoured John Bartholemew’s intricate maps for Cathkin Terrace; this part of Glasgow’s southside growing ever denser with each download. Hours were lost to this search yet this address stubbornly refused to be found. In the survey of 1858, only a handful of developments branch off from the trunk routes that will become Cathcart Road and Prospecthill Road. One of these branches will become our street, Queen Mary Avenue. The dotted lines indicate it is under construction at the time of the survey. The next survey was conducted in 1896 and I remember zooming in on section after section in the hope that Cathkin Terrace would appear. No such luck. I grudgingly accepted it must have been close to both Cathkin Park – historic home to 3rd Lanark Football team and now flanked on all sides by post-war council houses and new-builds – and Hampden Bowling Club which stands on the site of the first ever purpose-built football ground established in 1873 for Scotland and Queens Park FC.

Still, the 1881 Census had given me something to go on. 3 Cathkin Terrace was home to four families, of which the Lowthers were the largest. I speculated their move to Queen Mary Avenue meant the Lowthers were on the up. Perhaps Richard – a Commerical Traveller – had enjoyed success enough to enable him to move his family out of the flat and into a house? Or maybe it was Helen who encouraged the move with the insistence that a family of six needed more space as well as room for the domestic servant, 27-year-old Margaret Maxwell?

At some point following the move to Douglas Cottage on Queen Mary Avenue, they re-christened it Sutherland House and installed a new frosted glass panel in the front door etched with the Sutherland family crest. It is still our front door today. Here had started another unfruitful search to discover their connection to the region at the top of Scotland. Perhaps, like us, they just took a fancy to the iconography of wildcats and daggers? Or the motto, Sans Peur Virtus Sine Macula: Without Fear; Virtue Without Stain?

Thinking about the door prompts me to wonder what else they did to claim this house and garden as their own. I walk to the living room window and look over at the dank stumps and the pale sawdust that surrounds them. I picture them as fragile saplings –staked and tied – no taller than the surrounding shrubbery and hedges in the fledgling garden. Did Richard enlist the help of his elder sons, William and Frederick? Might the family have envisaged the trees growing with them; their planting imbued with the significance of new beginnings? I’ll never know. But it doesn’t stop me from fancying.

I return to the papers.

The 1881 Census listed the family by age and status. Their youngest son, Peter, was just two months old but this still ranked him above poor Margaret Maxwell. He would have been a baby at the time of the move, and I can imagine the hope and expectation that would have accompanied them all. It’s a feeling I’d had, too. It’s something we all do; place irrational faith in our homes as protector, refuge.

I remember a fizzing anticipation as the day of our moved approached. I’d take my chances between feeds to fill another charity shop bag or pack another box, all the while imagining how our stuff would work in the house we’d visited only once – in the dark – when our daughter was only weeks old. I decided that what the long-quiet house really needed was to be once again filled with noise. Chaos. Life. And while the old sofas never quite worked in the new living room, I have been granted my wish as far as the noise goes.

And now, my hands happen upon information I still remember the first clout of.

My baby daughter had been sleeping soundly in our temporary downstairs bedroom when another late night search of the archives turned up two death certificates issued to the Lowthers in brutal succession. First baby Peter, who died in 1883 of what they called ‘cerebral congestion,’ and then his father just four years later. This house hadn’t at all cosseted them from the bitter blows so often dealt to families living in Victorian Glasgow. Superstitiously, I crept in to hover a hand over my sleeping babe’s chest to check she was still drawing breath. Of course she was. I felt a fool. For this, and also for having invested so wholly in the fantasy that a sandstone structure had the power to insulate its inhabitants from the insidious dangers that lurked outwith or bred imperceptibly – fatally – within. But this was an irrational sadness. I was inhabited by a sense of loss that was not my own. I appealed to my rational mind. Yes, there were parallels. But we lived in different times, surely. This couldn’t happen to us, could it?

It would take COVID a few years later to rattle my foundations so strongly again. The democratising nature of a novel, invisible virus that devastated families without a care for wealth or status meant that the unvoiced fears that oftentimes kept me from my sleep became socially understood. I followed the news as it was pumped into our rooms from discrete smart speakers, registering the human cost of the pandemic. The death toll – staggering and ever-rising – was brought into focus through the stories of strangers who had lost their lives prematurely, in isolation, and with a speed that barely allowed the bereaved time to catch their breath. I became anxious to step over the threshold. Worried for my husband as he did the weekly shop. We were the lucky ones – I knew – with our house, our garden. But luck didn’t really come into it, did it?

We had become so unused to the threat of an early death. We had forgotten we lived for the first time in human history with the illusion of certainty about our life chances.

So what for the Lowthers? Just a typical family of that era. A family inured to loss. By the time of the 1891 census Helen was living here with her youngest daughter, Margaret, who at 13, was five years younger than her next oldest sibling. The live-in help long-gone too, likely beyond Helen’s means. Had her teenaged children branched out in the intervening years to make friends on the street? I’ve often wondered this knowing that the writer John Buchan, his sister, Anna (who later wrote under the pseudonym O. Douglas), and their three younger siblings were living down the hill at number 34. The house – with its grand copper beech tree towering over the front garden to this day – served as the manse for the John Knox Free Church in the Gorbals of which their father, Reverend John Buchan, was the minister. Their mother, also Helen – vividly portrayed in O. Douglas’s 1945 memoir Unforgettable, Unforgotten – could also very well have been a friend of the recently-widowed Helen Lowther. I’d skim-read O. Douglas’s words in search of something to link them:

Most women find a house and family quite enough to keep them busy, but besides visiting constantly in the congregation she started a Women's Meeting which met every Monday and took over a Bible Class for older girls on Sunday evening.

Might Helen Lowther have attended these Women’s Meetings? Or was I grasping at the flimsiest of details, desperate to make another connection? Perhaps these women had little in common? And yet. Perhaps the events of 1893 when the Buchan’s youngest daughter, Violet, was five became cause for one woman to reach down the street to the other?

Her fourth Christmas was particularly joyous... She seemed positively transported with happiness, watching the parcels arrive, helping Father to cut holly and ivy and decorate the house, trotting after Mother as she put out the extra silver and china that would be used, and trying to imagine what Santa would bring to her.

(…) That was Violet's last Christmas. She died, the beloved child, three months after her fifth birthday. Died at Broughton — the place that we had fondly believed could cure all earthly ills — as the dawn was breaking on a perfect June day.

Anna would no longer brush her little sister’s hair until it shone. No longer walk her around Queen’s Park or past the rows of shops on Victoria Road. Instead, she was to be sent off to boarding school in Edinburgh to grieve alone for her little sister. And though over a century separates us, I see that the impulse to put faith in the protective force of a house is a timeless one. We cling to whatever we can when hope is in short supply.

Another son was born to Helen and John Buchan soon enough. And might it have been a particular point of jealousy for Helen Lowther, for the boy who was christened Alasdair was known affectionately as Peter – the name of the Lowthers’ lost boy.

I flick to the next printed page of my search. It’s an advert, placed in the Glasgow Herald on Monday December 17th, 1894. I once circled it in yellow highlighter to make it stand out amongst the rows of tiny text common to newspapers at the turn of the 20th century, but even that has faded now. That Christmas, 29 Queen Mary Avenue was for sale by ‘Private Bargain’. Perhaps Helen could not justify living in a family-sized house any longer? Or perhaps this other Helen, down the street with her own little ‘Peter’, triggered an unbearable pain? Yet (in the absence of a buyer?) Helen did not leave in the winter of 1894.

Six years passed. By 1901, Helen Lowther and Margaret – then 24 and working as a clerkess – were living together at number 29. On the night of the count, Frederick was also home. He was listed on the Census as a Traveller, so was he just stopping by that night? In crude contrast to the non-family member listed in the household of 1881, 20 years later the Lowthers shared the house with a married couple: lodgers William and Janette Robinson. Post office clerks, they could have worked close by at the old Crosshill Post Office a five-minute walk away on Victoria Road. We don’t look up often enough in Glasgow. I blame the weather. Or the hurry we all seem to be in. We’d been here years before I noticed its faded signage still visible on the red sandstone lintel.

Maybe Helen had been forced to take lodgers when the house didn’t sell, I’d wondered. When I’d first discovered this detail, we – too – had a room to let in the house. I’d left teaching to be at home with my girls and money was tight. There was something of this story, though, that buoyed me. Made me see that it was alright. I needed that reassurance from a century before.

By 1911 it was all change, again. Frederick was here along with his mother, an old woman at 72. The Robinsons took flight at some point to lodgings at 23 Herriet Street in Glasgow’s ‘Garden Suburb’ of Pollokshields. In their place was Mary Livingston who, at 62, I imagined was hired more as a lady’s companion to provide the sort of company a younger, light-footed servant couldn’t begin to offer. I presumed that Frederick was living with his mother out of a mutual need. He needed looking after in the way a wife might have done for him if he’d been lucky. Helen may have needed a man to take care of the more challenging or physically demanding aspects of keeping a house going. Maybe she’d pictured Richard doing all of it for her back when they first moved in all those decades before? I could relate to that.

The Lowther era ended not long after the Great War began. Helen died at home of a cerebral haemorrhage in the early hours of the second of February 1915, aged 76. She did not live long enough to hear of the death of ‘Peter’ who lost his life at Arras on April 9th 1917. His death followed those of John senior and another brother, William. The Buchans – like the Lowthers before them – had become just another family bearing loss after loss.

Since Violet's death we had enjoyed years of health and prosperity. So well did things seem to work out for us that people talked of 'the Buchan luck,' and I used to look pityingly at people on whom blow after blow fell and wonder how they bore up at all. But few people get off unscathed, and our turn came.

In the aftermath of Alasdair’s death, Anna published a novel – The Setons – at her brother’s insistence. She wrote it for her mother. She sought to recreate the happy home life they had had on Queen Mary Avenue, she said.

“Come and sit on the bench!”

I put the sheaf of papers down, hearing this call from the front door. I check my watch as I ease myself from my spot on the rug. It’s getting on. The girls will be on their way home, but there is a wee sliver of time before one of us needs to walk the short distance to the bus stop on Cathcart Road. Time enough to sit on our ‘new’ bench. Feel for the first time the early spring sun on our faces now the trees no longer block it. Its rough bark now beneath our fingers.

“See!” My husband says, nestling his backside into a dip on the trunk, “Two perfect seats!” I can see he’s tickled he noticed these divots as he rolled the trunk into position under the bay window.

I rest my back on the cool blonde sandstone and close my eyes. We are quiet; lost in our own thoughts. Mine? On all that’s come before and the unknowable future that lies ahead. Today, we have witnessed an ending of sorts. But also, I must believe, a beginning. Or if that’s a stretch, at the very least a continuation. A continuation of this house’s story. Ours, too. It will be our job plant something else in their place for the next custodians to look after.

It’s our job, too, I think to myself, to act. What must we do beyond this front garden? Beyond our local park?

“What will our two say when they see the front garden in its new state?” I wonder aloud, gathering myself for the bus run.

“Absolutely nothing,” he replies. “Now, if we’d chopped down the swings…”

Thank you for letting me read this! Wonderful to 'meet' the Lowthers.

Such a beautifully written, poignant and mournful piece, Lindsay. I'm glad you followed your instinct and shared this with us instead this week.

Sounds like a fascinating journey you've been on to piece together the stories of your home. So much you'll never know but so much that would have been forgotten if it wasn't for this research you're doing.

And now you're living and creating its next chapters.

(P.S I also love old maps, not that I'm any good at reading them)