What we're not yet talking about when we're talking about mental health

I'm ready. Are you?

Welcome to What Now? with Lindsay Johnstone. I’m a writer, literary critic and workshop facilitator from Glasgow, Scotland. Last autumn, I ended a three-year psychotherapy journey asking myself, ‘What now?’

I vowed that I’d replace those thrice-weekly therapeutic hours with something, but wasn’t then sure quite what.

Enter Substack.

Here, most Sundays, I hold the necessary space for myself and others entering midlife while very much still figuring things out. This week’s letter is free to read, but for access to the archive, our Friday Chat thread, my courses and upcoming podcast excerpting my memoir, I’d be so delighted to welcome you into my Membership.

Hi friends,

I don't know about you but up until recently, I thought I was being open enough about myself and my work on social media. It turns out, though, I wasn’t. There was a filter between the truth and what I was prepared to disclose as the truth.

What I’ve been sharing over the past 10 days, over on my Instagram account, though, has shown me the veil needed lifting if I’m to connect with readers in the way I want. I’ve been holding back for fear that I’d give too much away of my memoir (read: me) before it’s published and because I've probably thought deep down that at a dreamy time in the future I’d be able to ‘afford’ showing my most vulnerable self.

However, having started to share the catalyst, process and deeply personal experiences that sit behind my memoir, I’ve had properly meaningful conversations with people about the gritty reality of my (and their) experiences of mental illness and caring. It's making me more certain than ever that we’re crying out for it, and that the book I needed to write is one I need to share, too.

The time for honesty is now.

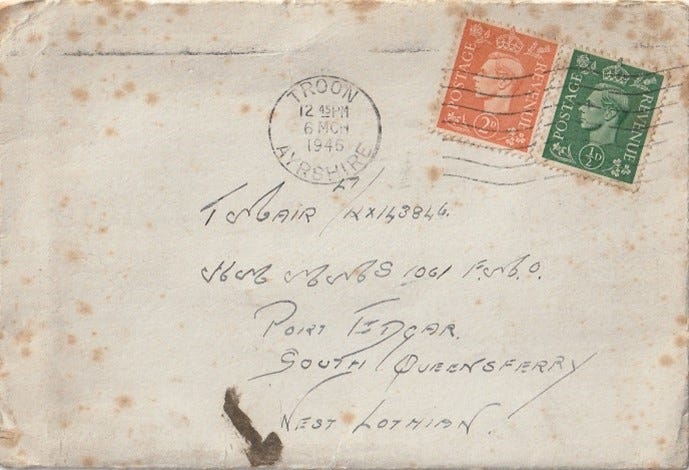

I started leaning into this nearly a fortnight ago on World Mental Health Day when I posted two pictures to my Instagram grid, along with a wordy comment. I’d taken the plunge after Caro Giles who writes Unschooled (and with whom I shared a beautiful half hour chatting all things caring and creativity a few months back for my member community) shared a vulnerable post about her experience of living with OCD. I loaded up my browser to write it because I knew I’d never be able to tinker as I’d wish on my phone.

Here’s what I posted:

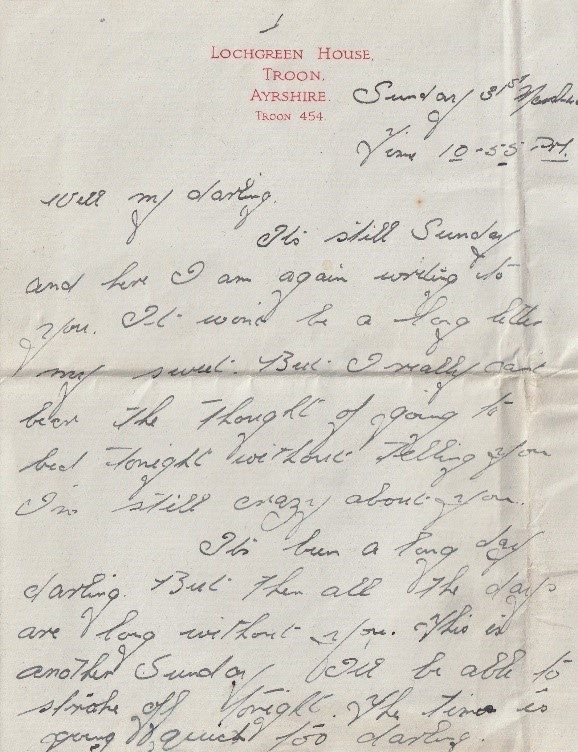

"With regard to your need to talk about your illness, this... can be somewhat off-putting to friends and acquaintances if it is overdone. If you do find that you are driving away your friends in this way, you could start to feel socially inadequate and that might not help your recovery... Try to school yourself not to talk about depression... unless someone else brings it up."

.

This #worldmentalhealthday I'm sharing one of the findings from my childhood home that propelled me to write my memoir about the legacy of intergenerational trauma. Listening to one another's experiences is the antidote to the stigma and shame that hounded all sufferers of mental health conditions even in our recent past.

My own experience of anxiety and panic didn't begin with me. It's a story whose origins go even further back than my mother's. I found this letter addressed to my mum from 1990 written in response to a letter she'd written upon being discharged from a long spell on a psychiatric ward where she was diagnosed with Manic Depression. I want to share it because it shows a young mother post-discharge desperately trying to understand her diagnosis and chart a way forward for herself and her young family, but with little hope of support offered beyond the medication she'd been prescribed following a course of ECT.

What strikes me in addition to the section I've quoted above is the way this (male) mental health professional tells her that her expectations of working again are unrealistic. That a doctor may be able to provide a letter of comfort to a prospective employer but that voluntary work would likely suit her best. Even the way he claims that she can forget all about her condition if the lithium works... The lack of understanding that early life trauma is at the root of many people's experience of poor mental health is astounding given what we now know and the way we treat the whole person, but also, how demeaning. She was discouraged from probing further. Encouraged to make her life small. And she did.Keep talking, friends. Please, keep talking.

In the hours that followed I was inundated by notifications of likes, shares, comments, DMs and voice notes. Friends, acquaintances and folk I don’t know at all were spilling their experiences of mental illness or having cared for someone suffering. The conversations that followed were both genuine and comforting.

Emboldened, I decided to mine this rich seam when taking part in writer Nicola Washington’s #SevenDayShare challenge, and got similar responses from people engaging with my words. For a writer in the hinterland between writing and publication, these sorts of discussions are so valued. They help remind us when spirits are low just why we were so compelled to write. Why we must continue to put words on the page.

Maybe more importantly, though, what these particular exchanges have reminded me is that we need to get better yet at talking about mental illness. I use the word illness deliberately. I use it instead of health.

I use it because I don’t think we are talking as honestly as we need to about the reality of living with debilitating, admission-worthy mental illness. Hard-to-keep-your-job mental illness. Sectionable mental illness. The so-called severe mental illnesses, including psychosis, schizophrenia and personality disorders. And what it’s really like to live with those who suffer.

In choosing to use this term, though, I’ve felt it necessary to check whether it's OK to do so, and hope that I’m getting this right for you. The UK charity, Mind, uses the term ‘mental health problems,’ but accepts that ‘mental illness’ can be helpful for some so I feel alright using it here and hope it's not triggering or heard in a way it isn’t intended to be.

My motivation comes from a need to distinguish the two terms. ‘Mental health,’ to me has become a woolly term. In some cases, almost meaningless. I’ve been saddened when I’ve heard people saying things like, ‘I’ve got mental health’ rather than what I think they mean to say: ‘problems with my mental health,’ because the stigma still exists.

I think that's problematic. Not only for the sufferer, who deserves language that is both fitting and helpful, but for us as a society. Many of us, you see, don't have or haven’t been in constant possession of our mental health. We have been mentally ill and it has to be OK to say that.

Yes, as a society we’re doing better. We've opened up the conversation around mental health and our need to protect it individually and societally, and we are developing a vocabulary that means it’s easier than it’s ever been to talk openly as sufferers of chronic mental health conditions. But still.

It’s not enough. It’s certainly not enough for me.

If I can be that vulnerable self for a moment, I’ll tell you that my most acute spells of mental illness almost landed me in hospital. In fact, perhaps I shouldn’t have been spared those admissions. I’ll tell you, too, at times I’ve felt ill-equipped to adequately mother my girls. I'll also tell you that the legacy of trauma lives on in me. It cannot be removed like a tumour (oh, how I’d wanted it to be taken out of me) and though therapy has enabled me to better accept these parts of myself, I must keep writing and talking to enable me to welcome rather than resist them.

My story may now be following a different trajectory to my mother’s and grandmother’s but I lived with these women. I am the genetic and environmental product (as are my girls) of this intergenerational story. Finding a cache of documents and letters at my childhood home a few years back served to flesh out our connected experiences in ways I could never have imagined. Our stories echo and collide across the generations in a house where sparks flew and tempers often flared. But while I’d been busy building a wall around myself as a means to insulate myself from what I’d feared would also be my fate, I would discover that I ignored what bound us at my peril.

My memoir weaves our three experiences of caring, mothering and being mothered while receiving treatments of various shades as patients within an imperfect mental health system. It sounds bleak, but it is, ultimately, a hopeful story. One that I think is helpful, too. I think this memoir opens up a much-needed space for conversation about the darker sides of mental illness for sufferers and their families. Shame thrives in the dark. When we shine our collective light into that blackness, we remove it of its power to scare us. To silence us.

What I love about Substack is that readers here can pick up with me whenever they like. By delving into the archive, readers get to know me better; piece the bigger story together. But equally, that weekly snapshot might hold something that resonates on its own.

In that spirit, I am getting ready to launch my podcast this November with short weekly excerpts from the book that stand alone as vignettes and also take their place as part of an epic intergenerational story. It’s a story I want to share here first, adapted for my Membership community on Substack. I hope that each excerpt acts as tinder for deeper conversations here with you, too. I’ll be sharing some of the documentation I relied upon to write it, and if you’re anything like me, this is where you'll find the magic and maybe even consider how to tell your story.

Are you with me?

In the meantime, please hop on over to Instagram to follow along with the last of the seven days of sharing, and get involved for a flavour of what’s to come here in a couple of weeks. I'm no Substack purist; I see the benefit of sticking around over there, too 😉

Until next week,

Lindsay x

“Shame thrives in the dark.”

So true and I appreciate the space you’re creating for conversation, and for people to share their deeper, darker experiences. As someone who has witnessed serious mental health problems take hold, and take the life of someone close to me, I am here for it 💛

I am so proud of you Lindsay. Your courage and honesty is already helping so many of us and your shining a light on the darkness is going to have so many positive ripples. I think the reaction you've had to sharing more shows how much the world needs your memoir.

You're also such a beautiful writer - your truth in your words is so powerful. Reading this it seems like you are also getting so much out of writing your stories down and using your creativity in this way.

This is no mean feat though. What you're doing is hard. I see you!