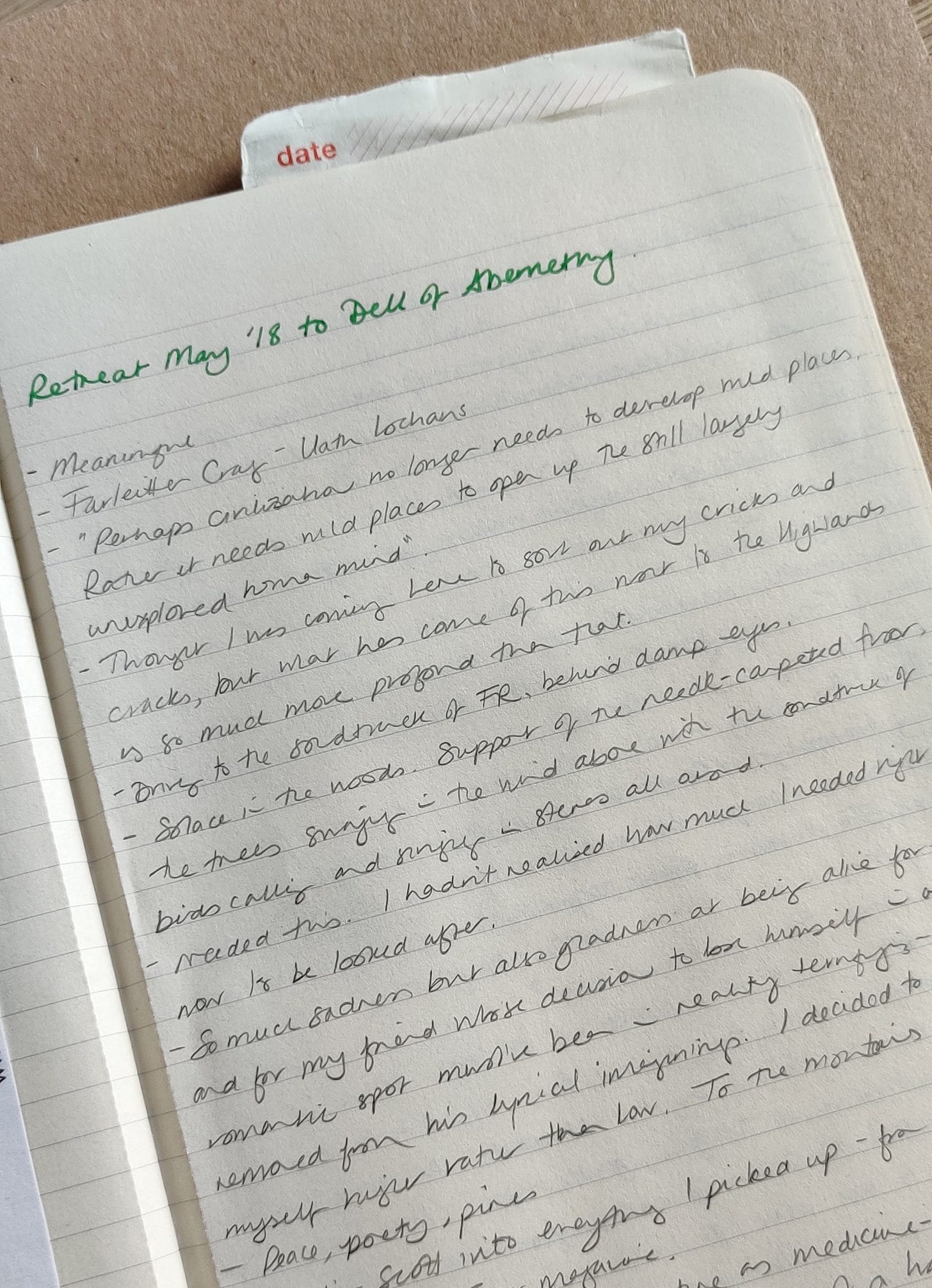

‘Perhaps civilization no longer needs to develop wild places. Rather it needs wild places to open up the still largely unexplored human mind.’

I copied down these words on the first page of the first journal I’d kept since adolescence. One I started on my first retreat to the Cairngorms five years ago. It was a week full of ‘firsts’.

In truth, I’d forgotten all about them until the other day when I took that small blue notebook down from the shelf it has sat on for nearly half a decade. After an unfruitful Google search to find out who said these wise words first, a rake through my photos from that time turned up this photo. Mystery solved.

My original plan had been to re-read the words I actually remembered having written at the end of that trip. I had an idea to share some of them with the delegates at the writing in nature workshop I’m leading in a fortnight’s time at The Summit on Arran, mindful of the compulsion I’d felt - softback book bent across my thigh, my bare feet dangling into the water at Uath Lochans - to commit my mind wanderings to paper and preserve the magic of the retreat.

But I’ve been struck by that quote. A quick scan might read like yet another warm and fuzzy invitation to step into wild spaces in order to reap nature’s many rewards. And this is indeed something I’ve come to rely on as a means of access to another part of my brain.

For going on retreat often opens the mind in unexpected ways. When we submit to a different rhythm for our days, enjoy meditation, group movement and being in nature, we might even be lucky enough to experience a flow state where – for a short time – everything feels imbued with significance. We see possibilities, connections, opportunities. Experience euphoria.

In this state, writing – and, of course, other creative expression - comes freely.

Perhaps you’ve noticed this before. Maybe you’ve gone out for a walk to clear your head in the middle of a busy day. Maybe you were able to get relief from troubling thoughts – even if only briefly – noticing the spring-cleaning power that can come from simply placing one foot in front of the other. Maybe you’ve been struck by a momentary inspiration or the realisation that a problem is suddenly solvable.

I can summon this state at will knowing, now, how to tune into myself but before I went on that first retreat I think it’s fair to say I didn’t really understand myself at all. In fact, as my journal pages reveal, I’d thought I was going to ‘sort out my cricks and cracks,’ only for it to become almost instantly apparent that the experience would be far more profound. The cracks were not only physical – the legacy of nearly a decade of childbearing and rearing – but mental. Emotional. And they ran deep. I had two young daughters, a caring responsibility to my mum and was shoehorning work around them all, tutoring and running an Airbnb as well as devising and delivering a family learning programme for the council. Steven worked full time, and so I did the bulk of the cooking, cleaning and shopping. I also carried what I think we still call the mental load; making and keeping appointments, buying birthday presents, planning childcare and so on.

Despite being ordered not to, I had cleaned the house, set out uniforms and filled the fridge before I left for the retreat. It was my birthday present, this time away. A gift unlike any I’d been given before. “Mum’s crying with happiness because she won’t have to do the cooking,” my then seven-year-old daughter had said when I’d been given the news. This was partly true. I was also crying in disbelief. And sadness, actually. That I was so desperate to escape broke my heart.

I’d also been struggling with anxiety and panic attacks, though of course, I couldn’t see that anything of my circumstances was influencing my fragile mental state. Instead, I just believed I was dying. Of course.

And then, just before I left, someone did die.

I travelled to the Cairngorms the day after the body of an old acquaintance was discovered at Port Edgar in the Firth of Forth. He too had suffered from anxiety, depression and panic attacks throughout his adult life. While close relationships, creative expression and time in nature had been crucial in helping him during periods of ill health, ultimately, nothing and no one could save him .

As I drove away from Glasgow that May morning, crossing the Highland boundary fault line into the mountains, I listened to the tributes on Radio Scotland’s mid-morning show pouring in for him and for his band’s music. What struck me was that there were far too many regretful voices that morning. Regret for the music that would go unmade, for the commercial success that would go unclaimed and, most importantly, for the life that was over that no one and nothing could save. And all the while, talk of men’s mental health. The unacceptably high suicide rate in Scotland and beyond.

He’d made a journey of his own in the days and hours before his death. Visited pals in the East Neuk; country-crossed to Mallaig and back again to South Queensferry. By all accounts, he’d seemed buoyant. Unburdened. It made the shock of his death harder to bear for those who’d spent time with him in his final days.

I can’t speak to anyone else’s experience, but I do wonder about that moment of transition back to real life after being part of something transformative, whatever that might have been. We might leave reluctantly, concerned about what might happen to our sense of peace, calm, capability, creativeness when we are - again – responsible for others. Consumed by work. Subject to myriad outside influences. Because there are no promises that the feelings will last.

In fact, it may be even more than just trepidation. Maybe there’s fear that we’ll come crashing down. That what we have gained will be lost. That real life will seem impossible, especially in the face of what others might expect from us now we’ve been ‘recharged’ or ‘healed’. Even the thought of the mess - the disorder - I anticipated finding at home upon my return was stressing me out. Steven, you see, had his priorities straight. He prioritised (still does, better than me) enjoying the kids over getting the tasks done.

To be clear, I was never suicidal. In fact it was an abject terror of death that dominated my thoughts in those days. However, despite my own challenges, I experienced that retreat in technicolour. Was this in part because the death of someone I had known imbued the everyday with the miraculous? Or that I was - for the first time in a long time - without any responsibility?

So there’s a warning of sorts here about what to expect afterwards. To anticipate complicated feelings. Overwhelm. An impulse to delay the return to the life that awaits you, no matter how good a life it is.

I’ve been reading Real Self-Care by American psychiatrist Dr. Pooja Lakshmin who argues that self care is NOT about the external - the singing bowls, the 10 minutes of meditation, even the retreat - but is instead a lifetime-long commitment to honour an internal pledge. She calls the bolt-ons ‘faux-care’:

It’s faux because it’s not sustainable, not self-directed. It’s faux because it exonerates the oppressive social structures that come from every direction and conspire with each other — patriarchy, white supremacy, toxic capitalism. It’s faux because it places the burden on the individual instead of calling for systems reform. This of course all comes back to race, class and privilege.

Unfortunately, a society based on speed and production is also one that is frightened of real-self care. Because it demands a slowing down. Being rather than doing. Shifting responsibility away from us to do it to them to facilitate it, whoever they may be for you. Have you ever felt guilt when we don’t do what we’ve been told we should to maintain good mental health? ‘Yes, I do have the Headspace app,’ we might say apologetically to the GP, ‘I know I just need to open it more often…’ It’s not that we don’t want to help ourselves. It’s that to do so requires a monumental shift - individually and societally - that sanctions the viewing of each decision through a self-care lens. Honestly, how often do we ask ourselves, What will the impact on me be from this? I still don’t, consistently. It leads me into situations I then have to extricate myself from, or where I feel resentment or a sense of obligation that takes up far more energy than it deserves.

Lakshmin asks a few pertinent questions for women, in particular:

Why don’t we ask ourselves the hard questions like: What am I trying to control with my addiction to productivity? Why do I believe that more is better? Why am I trying to optimize my “rest”?

It’s making me wonder about our culture’s current obsession with imposing order, tidying up and chucking out. We’ve been conditioned to believe that only when we’ve spent time, money and effort on the external will we be able to access our calm selves, experience freedom, or tap into our creativity. This leads us to invest in the myth that tidying up is a feminist act. Tell ourselves that we’ll do the yoga when the house is sorted. Or if we do make self-care a priority, we compartmentalise it into long-anticipated, pressurised weekends.

By all means, GO ON THE RETREAT. But ensure, too, that a return home is planned-for. That there is time to process what has shifted to successfully integrate these changes into your ‘real’ life, rather than seeing the weekly yoga class or the cost of the meditation app as heaping yet more pressure to ‘do’ upon you. On a practical level, can someone at least be primed to make the dinner for your return?

And I return to those quoted words. Perhaps the author was criticising the practice of ‘re-wilding’? This isn’t the newsletter for that debate. Or perhaps he was suggesting that our power lies in stepping into the wild that is already there rather than waste time contriving a utopia of sorts, whether that be ancient forest land or an Instagram-ready storage solution for the kitchen? I write this having dumped the laptop on a pile of old newspapers at my end of the dining table, barely bothered by the mess even though the kids’ end is a complete riot with just enough space for them to eat their dinner at this evening. There are currently two house bunnies under my feet; their area no longer distinguishable from ours. Hay and sawdust everywhere. There’s a wash to put away and dishes still to do. But not one of these jobs is ‘mine’. Or at least not mine alone. And I know that it helps no one for me to martyr myself.

All this is more normal for me these days, having let go of the compulsion to prioritise controlling my space in lieu of my mind. It would have felt unthinkable to me a few years ago that I could get anything for me done having not yet cleared the decks. Taking time to notice this and reflect on how things used to be tells me that I’m better. That I’m honouring my ongoing commitment to real self-care. And that brings a greater benefit to me and those I love than a tidy table ever will.

So I just came across you, Lindsey, responding to Tim Lott, and this was a wonderful read for me, today. I tend to pack my weekends full in anticipation that I will feel I’ve done something ‘for me’ - and that image of stuff not put away resonates! F time work and a partner who rightly sees life in more balance than me, and has fun (being homo ludens a man of play) - lucky him- means I’ll tidy the mess that is the house, before I get down to writing. Which is my ‘holy graile’ - time and space to write.

Thank you also Fiona - for the honesty and mentioning guilt, impending caring duties, stuff like washing not put away and so on. Messy table-mine is rarely not - whatever I do. It’s everyone else’s too. (VW and her Room comes to mind).

Great phrase! Controlling my space- instead of my mind.

The house is messy yes it is, but I have time to type a story I wrote. About freedom and thought and love. Going there now. Thanks again, for voicing your impressions. 😊

Real self-care is on my list. I like this reminder to take the slow back into the everyday.