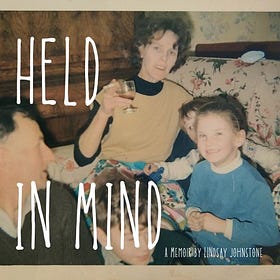

Held in Mind: a Memoir

New to my audio memoir on disrupting the cycle of intergenerational maternal trauma? Start here...

“This is stunning. Memoir is such a fascinating genre isn’t it? And you write it brilliantly.”

Clover Stroud – author of four memoirs including the Sunday Times Bestseller, The Giant on the Skyline

In the absence of a ‘well’ mother, can it ever be possible to become a ‘good enough’ one yourself? Does mothering your own mother risk an inability to adequately meet the emotional needs of your children? This is a memoir about intergenerational trauma, dependency and loss. It is about the consequences of allowing yourself to be held in mind while you try to hold onto the ones you love.

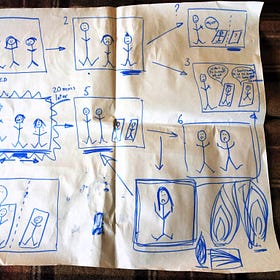

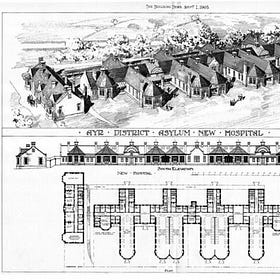

In 2019, Lindsay embarks upon a therapy journey that coincides with never-seen-before discoveries at her childhood home. Together, these reveal she is the latest in a long maternal line living with a mental health condition and the legacy of trauma. Lindsay’s story, along with those of her mother and grandmother, echo and collide across the generations under the shadow of deadwood in a house where tempers flared and sparks flew.

Will therapy give her the tools to undo unhelpful coping mechanisms of a lifetime? Will she allow herself to be vulnerable in a way that will see her mental health and relationships heal? Will the scars of the past ever fade or is she destined to inflict similar wounds upon the next generation, no matter what she does?

Exclusive to Lindsay's Substack Members' community, listen here now:

Held in Mind: A Memoir

What are the consequences of allowing yourself to be held in mind while you try to hold on to the ones you love?

Episode Eleven: A 'good case'

There is so much here for smart, creative women from this smart, creative woman, plus I have only just discovered Lindsay reading extracts from her powerful memoir – I am already hooked (and now a complete fan of her work)

Episode Twelve: The Supervisor

How should you ‘be’ during a meeting with your therapist’s supervisor where your suitability for more intensive talking therapy is assessed?

Episode Thirteen: Paris

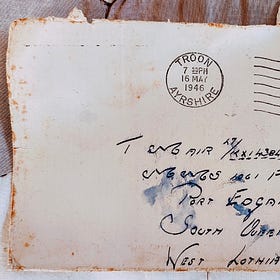

In the letters, Helen makes it clear to Tom that she won’t tolerate drunkenness in her husband. His ship has relocated from Granton to Port Edgar, South Queensferry, though he’s impatient for word of his demob.

Episode Fourteen: The Twins

“This is stunning. Memoir is such a fascinating genre isn’t it? And you write it brilliantly.”

Episode Seventeen: 1997 and 1974

I adore Lindsay's energy, her honesty, and the way she captures the depth of some of the darkest moments in life and writes about it with such beauty. A tonic for today. Lauren Barber

Episode Twenty Two: Drinking in Dublin

“This is stunning. Memoir is such a fascinating genre isn’t it? And you write it brilliantly.”

Episode Twenty Four: Any Human Heart

Before the trip, Lindsay reflects on the events of May 2014 and a panic attack that tricked even the professionals into thinking something far more sinister was going on. Six years on, does she really believe that they got it right in the end?

Episode Twenty Seven: Surgery

“This is stunning. Memoir is such a fascinating genre isn’t it? And you write it brilliantly.”

Episode Twenty Eight: Containment

“This is stunning. Memoir is such a fascinating genre isn’t it? And you write it brilliantly.”

Episode Thirty Seven: Fuck Porridge

“This is stunning. Memoir is such a fascinating genre isn’t it? And you write it brilliantly.”

Episode Forty Three: PS

For the more haunted among us, only looking back at the past can permit it finally to become past.

Oh that wall! Immediately John Mellencamp's Crumblin Down chorus started playing in my ears. Just like doors opening and shutting, walls going up or crumbling down are tantalizing metaphorical material. What a wonderful thing to have, your grandparents love letters! I have one parallel but not as close as yours. I happen to work down the street from a church in Boston that my Welsh 7th great grandfather was a founding member of. I had been taking walks around that church for awhile (I love circumambulating places ... I feel like it gins up energy and grounds me) and then on a weird parallel whim launched in to a genealogical search... That's when I discovered that I had been walking around the same hill these ghosts walked in the 1630s. Looking forward to your next post!

To echo Kerri’s thoughts, you’ve stumbled upon some real gifts here in these letters and, together with your writing, the book will be a beautiful read for others!